Understanding the State Design Pattern

• • 20 min readThere are 23 classic design patterns described in the original book *Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software*. These patterns provide solutions to particular problems often repeated in software development.

In this article, I am going to describe how the State pattern works and when it should be applied.

State: Basic Idea

Wikipedia provides us with the following definition:

“The state pattern is a behavioral software design pattern that allows an object to alter its behavior when its internal state changes. This pattern is close to the concept of finite-state machines. The state pattern can be interpreted as a strategy pattern, which is able to switch a strategy through invocations of methods defined in the pattern’s interface.” — Wikipedia

On the other hand, the definition provided by the original book is as follows:

“Allow an object to alter its behavior when its internal state changes. The object will appear to change its class.”

On many occasions, we have an object which has a behavior depending on the state in which it is found. For example, when we have a purchase in an ecommerce, this purchase is started, processed, shipped, delivered, etc. The system would work differently depending on the state it is in, and this is precisely where the state design pattern can help us make our code more flexible and maintainable.

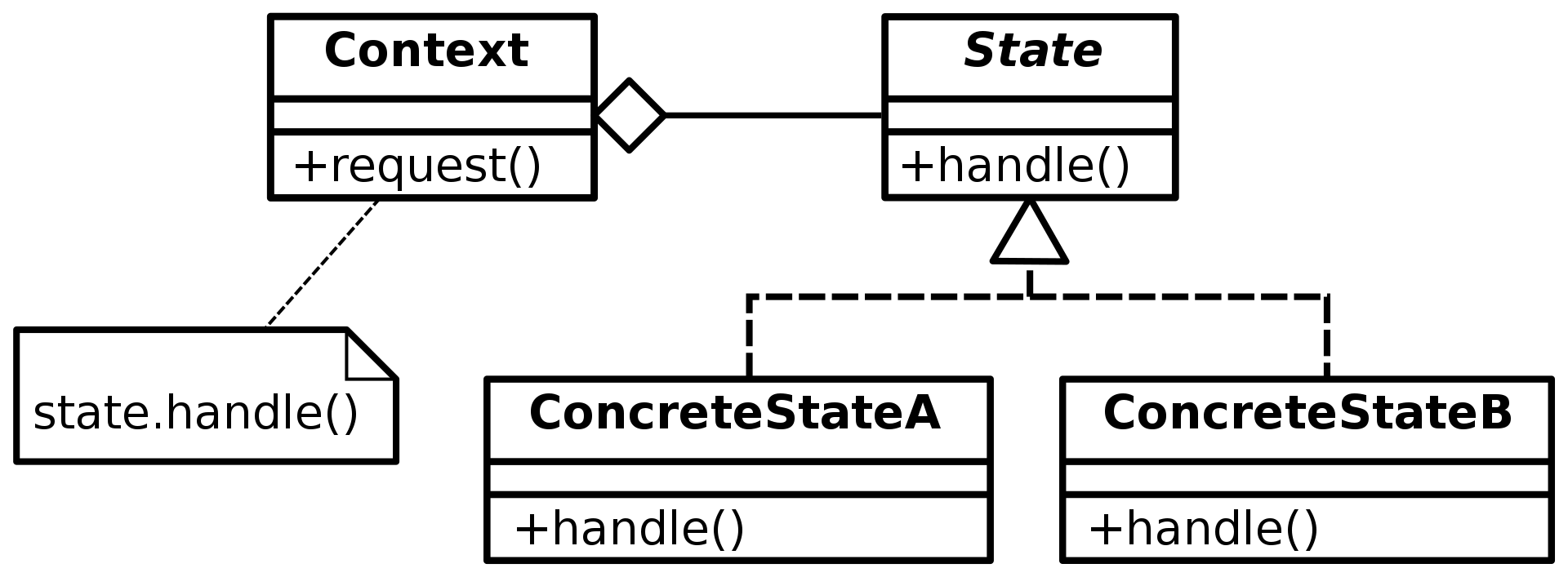

Next, let’s look at the UML class diagram of this pattern to understand each of the elements that interact in this pattern.

These are the classes that comprise this pattern:

Contextis the interface of interest to clients. This class maintains an instance of aStatethat defines the current state.Statedefines the interface for encapsulating the behavior associated with a particular state of theContext.ConcreteStateAandConcreteStateBare the subclasses that implement a behavior associated with a state of theContext.

State Pattern: When to Use It

The state design pattern has the following use cases:

- An object’s behavior depends on its state, and it must change its behavior at runtime depending on that state.

- Operations have large, multipart conditional statements that depend on the object’s state. This state is usually represented by one or more enumerated constants.

- The State pattern puts each branch of the conditional in a separate class. This lets you treat the object’s state as an object in its own right that can vary independently from other objects.

State Pattern: Advantages and Disadvantages

The State pattern has a number of advantages, summarized in the following points:

- The code is more maintainable because it is **less coupled** between the object and its states. The object (

context) only needs to know that there is aStatewhich will be handled using theStateinterface. - Clean code. The Open-Closed Principle (OCP) is guaranteed since new states can be introduced without breaking the existing code in the chain.

- Cleaner code. The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) is respected since the responsibility of each state is transferred to its

ConcreteStateclass instead of having that business logic in theContext.

Finally, the main drawback of the State pattern — like most design patterns — is that there’s an increase in code complexity and the number of classes required for the code. With that said, this disadvantage is well known when applying design patterns — it’s the price to pay for gaining abstraction in the code.

State Pattern Examples

Next, we are going to illustrate with two examples of the State pattern:

- The basic structure of the State pattern. In this example, we are going to translate the theoretical UML diagram into TypeScript code to identify each of the classes involved in the pattern.

- The change of state of an anime character, such as the villain Freeza from Dragon Ball Z which can change its physical state through different transformations. In our case we will have up to five different states changes. Bearing in mind that between states it is possible to advance or go back one level of the transformation. However, we should have generated the state machine that we would have wanted in this process of transformations.

The following examples will show the implementation of this pattern using TypeScript. We have chosen TypeScript to carry out this implementation rather than JavaScript. The latter lacks interfaces or abstract classes, so the responsibility of implementing both the interface and the abstract class would fall on the developer.

Example 1: Basic Structure of the State Pattern

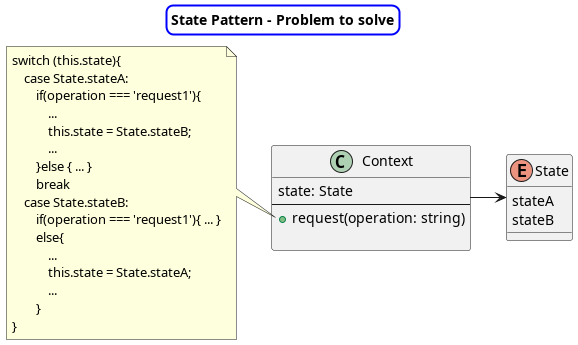

First of all, we can see the UML class diagram of what the implementation would be like without using the State pattern and the problems that it tries to solve.

In this diagram we can see that we have a Context class, which corresponds to the object that has different behaviors depending on the state it is in. These states can be modeled through an Enum class where we would have different possible states, as an example we would have two different states: StateA and StateB.

The request method of the Context class is where the open-closed principle is breaking since this method implements functionality based on the state the Context object is in. In addition to this, this method receives as a parameter a type of operation which adds conditional complexity to our problem. Even if we were to extract the behaviors of each state to external functions, we would still break this principle since every time we wanted to include a new state we would have to access this method and modify it.

Let’s see the implementation of this code to see it materialized in a programming language.

import { State } from "./state.enum";

export class Context {

private state = State.stateA;

request(operation: string) {

switch (this.state){

case State.stateA:

if(operation === 'request1'){

console.log('ConcreteStateA handles request1.'); //request1()

console.log('ConcreteStateA wants to change the state of the context.');

this.state = State.stateB; // Transition to another state

console.log(`Context: Transition to concrete-state-B.`);

}else {

console.log('ConcreteStateA handles request2.'); // request2()

}

break

case State.stateB:

if(operation === 'request1'){

console.log('ConcreteStateB handles request1.'); //request1()

}else{

console.log('ConcreteStateB handles request2.'); //request2()

console.log('ConcreteStateB wants to change the state of the context.');

this.state = State.stateA; // Transition to another state

console.log(`Context: Transition to concrete-state-A.`);

}

default: // Do nothing.

break

}

}

}

In this code we can see in the request method how the switch control structure is implemented, which couples the code to the Context states. Observe that the state change is done in this method itself, when we change the state we are changing the future behavior of this method since the code corresponding to the new state will be accessed.

The client code that would make use of this code is to implement the following.

import { Context } from "./context";

const context = new Context();

context.request('request1');

context.request('request2');t

You can see that we simply instantiate an object of type Context and call the request method with different parameters. Obviously, although the result of this code is what we expect, we have all the design problems that we have mentioned above.

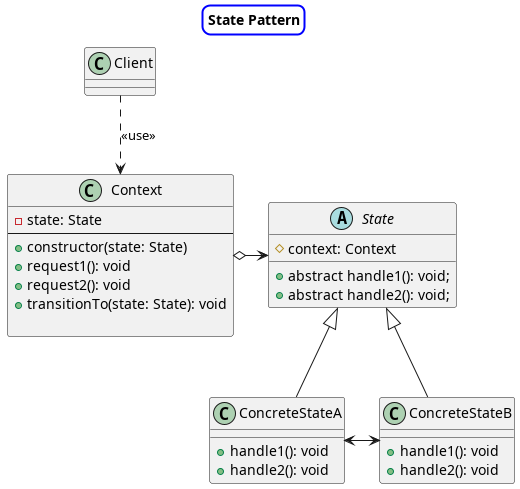

Now we are going to focus on solving this problem by applying the State pattern. Let’s start by looking at the class diagram.

The Context class is now related by composition to a new object that is the State of the context. The Context will still have methods associated with the functionality it performed previously, such as request1 and request2. Also, a new method, called transitionTo is added that will transition between the different states. That is, the change from one state to another will be done through a method that encapsulates this logic.

The Context class is related to an abstract class called State, which defines the contract that all possible states of our context must fulfill. In this specific case, two abstract methods handle1 and handle2 are defined, which will be specified in the concrete implementations of each of the states. That is, we are delegating the responsibility of implementing the behavior of each state to a specific subclass of said state.

On the other hand, the state class incorporates a reference to the context to be able to communicate with it to indicate that it must change its state. This reference in many implementations of the pattern does not exist, since the context reference is sent as a parameter to the methods defined in the state. We have preferred this implementation, which still respects the concept of composition and will greatly simplify the code we are showing.

Once we have seen the UML class diagram, we are going to see what the implementation of this design pattern would look like.

import { State } from "./state";

export class Context {

private state: State;

constructor(state: State) {

this.transitionTo(state);

}

public transitionTo(state: State): void {

console.log(`Context: Transition to ${state.constructor.name}.`);

this.state = state;

this.state.setContext(this);

}

public request1(): void {

this.state.handle1();

}

public request2(): void {

this.state.handle2();

}

}

We start by looking at the Context class, and the first thing we can notice is that the state attribute is an object of the State class, rather than an Enum class. This State class is abstract so that responsibility can be delegated to concrete states. If we look at the request1 and request2 methods we see that they are making use of the state object and delegating responsibility to this class.

On the other hand, we have the implementation of the transitionTo method which we are going to use simply to change the state in which the Context is, and as we have already said to make it easier for us not to propagate the context through the handles of the state object, we are going to call the setContext method to assign the context to the state, making the communication between state and context permanent rather than through references between the methods.

The next step is to define the part corresponding to the states. First we see that the State abstract class simply defines the abstract methods that the concrete states will implement and a reference to the context.

import { Context } from "./context";

export abstract class State {

protected context: Context;

public abstract handle1(): void;

public abstract handle2(): void;

}

The concrete states are those that encapsulate the business logic corresponding to each of the states when the context object is in them. If we see the code associated with these classes, we can see how the ConcreteStateA and ConcreteStateB classes implement the handle1 and handle2 methods corresponding to the State interface, and how in our specific case we are transitioning from StateA to StateB when handle1 is executed when the context is in the StateA . Whereas, we transition from StateB to StateA when handle2 is executed when the contextis in the StateB.

In any case, this is just an example of transitions between states, but it is important that you note that the states know each other, and that is a differentiating element of this design pattern compared to others such as the strategy pattern, in which the strategies do not know each other.

import { ConcreteStateB } from "./concrete-state-B";

import { State } from "./state";

export class ConcreteStateA extends State {

public handle1(): void {

console.log('ConcreteStateA handles request1.');

console.log('ConcreteStateA wants to change the state of the context.');

this.context.transitionTo(new ConcreteStateB());

}

public handle2(): void {

console.log('ConcreteStateA handles request2.');

}

}

/*****/

import { ConcreteStateA } from "./concrete-state-A";

import { State } from "./state";

export class ConcreteStateB extends State {

public handle1(): void {

console.log('ConcreteStateB handles request1.');

}

public handle2(): void {

console.log('ConcreteStateB handles request2.');

console.log('ConcreteStateB wants to change the state of the context.');

this.context.transitionTo(new ConcreteStateA());

}

}

To conclude, we see the client class that makes use of the design pattern.

The code is almost the same as the one we had without applying the pattern except that now we are creating an initial state with which the context will be initialized.

import { ConcreteStateA } from "./concrete-state-A";

import { Context } from "./context";

const context = new Context(new ConcreteStateA()); // Initial State

context.request1();

context.request2();

Example 2: Dragon Ball Z: Freeza Transformation

In this example, we are going to model a Dragon Ball videogame in which we would have a beloved villain such as Freeza, who, as we know, can undergo different transformations throughout a battle.

That is to say, we will have a character called Freeza which has different states that are the transformations in which they are found, this state can change as Freeza is winning or losing in the battle. In our case, Freeza will start with a state of Transformation1 and will be able to change his state to Transformation2. At that moment, the transition between states can be to return to Transformation1 in case he is winning in battle or transition to the state of Transformation3. In transformation state number 3 the same thing will happen and we can transition to Transformation2 or Transformation4. Finally, when we are in Transformation4 we can return to Transformation3 or transition to the state of Golden Freeza which will be the last possible state, from which we can only go backwards.

Obviously in our model we are moving back and forth, but the state machine that we can build can transition through the states as our business logic determines.

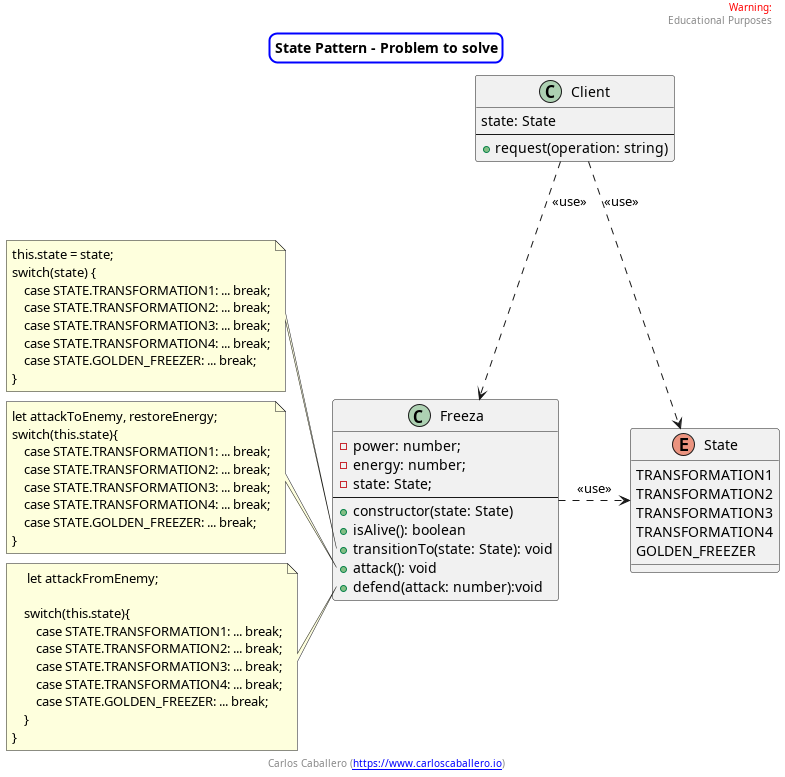

Let’s see what the class diagram for our problem might look like without applying the state design pattern.

The different STATES have been modeled with an Enum. That is, we will have an enum class where the different possible states that Freeza can go through are described. On the other hand, we have the Freeza class that models our character, this class is made up of various attributes such as power, energy and state. Both power and energy help us determine when to change state, and are part of the game. The methods by which Freeza is composed are:

Constructorthat receives the initial state of Freeza.isAlivethat will return a boolean value to know if Freeza is still alive.transitionTo,attackanddefend, which are the ones with the logic associated with each of the possible states. ThetransitionTomethod modifies theenergyandpowervalues depending on the state in which Freeza is, in the same way attack and defend determine the power with which Freeza attacks and defends itself, which is determined by the state in which is found.

We have left as a note in the UML diagram that these methods are developed from a switch-case structure in which each of the cases of this structure implements the desired behavior.

Of course, here we can see how both the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) and the Open/Closed Principle (OCP) are violated since. First of all, SRP is violated because we have different behaviors modeled in the same class or method. Secondly, the OCP is violated because if we wanted to introduce the new Freeza transformation we would have to modify this class, and as we want to introduce new features we are forced to modify this class.

Well let’s see the concrete implementation of our problem to see how all this would be translated into code.

First of all, we see the State enum that, as we have said, only defines the different states through which Freeza can transition.

export enum State {

TRANSFORMATION1 = 'transformation1',

TRANSFORMATION2 = 'transformation2',

TRANSFORMATION3 = 'transformation3',

TRANSFORMATION4 = 'transformation4',

GOLDEN_FREEZA = 'golden_freeza',

}

The next step is to look at the Freeza class, which has the attributes we’ve already mentioned above, and this has little to add. If we look at the constructor we can see that receiving a state that Freeza is in, we transition to that state. Another method that we have implemented is isAlive which checks if the Freeza energy is still greater than zero.

On the other hand, when we look at the transitionTo method, this is where code-smells can be detected or how the two SOLID principles are violated, since we see that this method modifies the energy and power values according to the state in which the object is found, and even if we extract this logic to auxiliary functions or methods, the logic of each of the states will still be there. That is, we will have five different states modeled in the same method.

The situation is aggravated if we see the code associated with the attack method. We once again have a switch to determine the business logic according to Freeza’s state, but as we can see, although this business logic is simple since they are simple mathematical calculations that determine the force with which it attacks an enemy, and the energy which is restored on each of your turns.

Finally, and in the same way as attack, the defend method is defined, which will again have a business logic based on the state of Freeza, but in this business logic we see that we have the transition between states. For example, in the state associated with Transformation2, if the energy value of Freeza exceeds 20, it transitions to Transformation3, and on the other hand, if the energy is 5, it transitions to Transformation1.

As you can see, this class makes us set off all the alarms that we need some refactoring technique.

import { State } from "./state.enum";

export class Freeza {

private power: number;

private energy: number;

private state: State;

constructor(state: State) {

this.transitionTo(state);

}

isAlive(): boolean {

return this.energy > 0;

}

public transitionTo(state: State): void {

console.log('-----------------------------')

console.log(`Freeze: Transition to ${state}.`);

console.log('-----------------------------')

this.state = state;

switch(state) {

case State.TRANSFORMATION1:

this.power = 530000;

this.energy = 5;

break;

case State.TRANSFORMATION2:

this.power = 106000;

this.energy = 10;

break;

case State.TRANSFORMATION3:

this.power = 212000;

this.energy = 15;

break;

case State.TRANSFORMATION4:

this.power = 106000;

this.energy = 20;

break;

case State.GOLDEN_FREEZA:

this.power = 212000;

this.energy = 30;

break;

}

}

public attack(): void {

let attackToEnemy, restoreEnergy;

switch(this.state){

case State.TRANSFORMATION1:

attackToEnemy = Math.round(this.power * (Math.random()/8));

restoreEnergy = Math.round(Math.random());

this.energy = this.energy + restoreEnergy;

console.log('Freeza attack in the state form 1 -->', attackToEnemy);

console.log(`Freese restore energy ${restoreEnergy} and his energy is ${this.energy}\n`);

break;

case State.TRANSFORMATION2:

attackToEnemy = Math.round(this.power * (Math.random()/7));

restoreEnergy = Math.round(Math.random() * 2);

this.energy = this.energy + restoreEnergy;

console.log('Freeza attack in the state form 2 -->', attackToEnemy);

console.log(`Freese restore energy ${restoreEnergy} and his energy is ${this.energy}\n`);

break;

case State.TRANSFORMATION3:

attackToEnemy = Math.round(this.power * (Math.random()/6));

restoreEnergy = Math.round(Math.random() * 3);

this.energy = this.energy + restoreEnergy;

console.log('Freeza attack in the state form 3 -->', attackToEnemy);

console.log(`Freese restore energy ${restoreEnergy} and his energy is ${this.energy}\n`);

break;

case State.TRANSFORMATION4:

attackToEnemy = Math.round(this.power * (Math.random()/5));

restoreEnergy = Math.round(Math.random() * 4);

this.energy = this.energy + restoreEnergy;

console.log('Freeza attack in the state form 4 -->', attackToEnemy);

console.log(`Freese restore energy ${restoreEnergy} and his energy is ${this.energy}\n`);

break;

case State.GOLDEN_FREEZA:

attackToEnemy = Math.round(this.power * (Math.random()/4));

restoreEnergy = Math.round(Math.random() * 5);

this.energy = this.energy + restoreEnergy;

console.log('Freeza attack in the state Golden Freeza -->', attackToEnemy);

console.log(`Freese restore energy ${restoreEnergy} and his energy is ${this.energy}\n`);

break;

}

}

public defend(attack: number): void {

let attackFromEnemy;

switch(this.state){

case State.TRANSFORMATION1:

attackFromEnemy = Math.round(attack * (Math.random()));

this.energy = this.energy - attackFromEnemy;

console.log('Freeza defend in form 1');

console.log(`Freeza received an attack of ${attackFromEnemy} and his energy is ${this.energy}\n`);

break;

case State.TRANSFORMATION2:

attackFromEnemy = Math.round(attack * (Math.random()));

this.energy = this.energy - attackFromEnemy;

console.log('Freeza defend in form 2');

console.log(`Freeza received an attack of ${attackFromEnemy} and his energy is ${this.energy}\n`);

if(this.energy < 5){

this.transitionTo(State.TRANSFORMATION1);

}

if(this.energy > 20){

this.transitionTo(State.TRANSFORMATION3);

}

break;

case State.TRANSFORMATION3: /* more code*/ break;

case State.TRANSFORMATION4: /* more code*/ break;

case State.GOLDEN_FREEZA: /* more code*/ break;

}

}

}

Lastly, we are going to finish by showing the code associated with the client. If you notice we only have one loop while Freeza is alive, Freeza attacks, waits a second, then Freeza defends, and so on until Freeza is no longer alive.

import { Freeza } from "./freeza";

import { State } from "./state.enum";

const sleep = (ms: number) => new Promise((r) => setTimeout(r, ms));

const freeza = new Freeza(State.TRANSFORMATION1); // Initial State

(async () => {

while(freeza.isAlive()){

freeza.attack();

await sleep(1000);

freeza.defend(10);

await sleep(1000);

}

})();

Example 2: Dragon Ball Z: Freeza Transformation (State Pattern)

We already have the context of the problem that we want to solve, now we are going to see how we can refactor the previous coupled code in a new version that will allow us to have the code with greater cohesion and allowing us to extend the project without violating the open-closed principle.

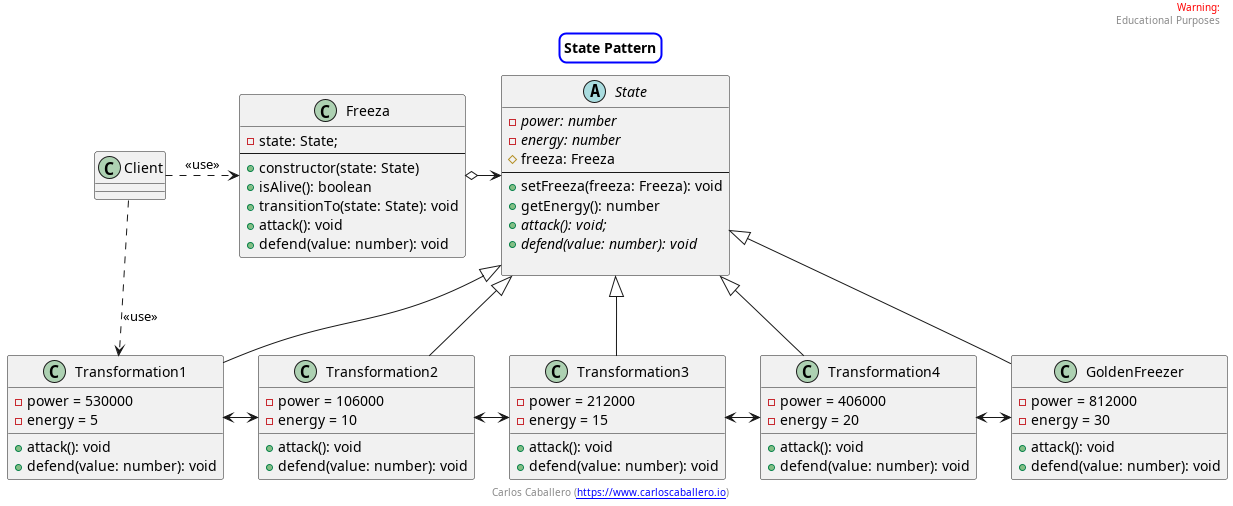

So the first thing we do is see what our project’s UML class diagram would look like by applying the state pattern.

We start by seeing that the Freeza class has the same methods as in the solution without applying the pattern. However, we can see that we now have a State attribute that, unlike in the previous solution, which was an enum, will now be an abstract class that represents the state of Freeza at a given moment. Very important, instead of being in the Freeza class, the power and energy attributes have been delegated to the State class because these two attributes change depending on the state in which the Freeza is. If any of these attributes or another attribute were not dependent on the state of the Freeza transformation, it would be in the Freeza class.

On the other hand, the novelty in this class diagram is that the State is now an abstract class that models the common attributes that each of the possible states in which Freeza is in will have, and defines the methods that encapsulate business logic different for each of the states that Freeza is in.

Therefore, we can see that we have the power and energy attributes defined as abstract because each of the concrete states will modify them depending on the state that Freeza is in; and here, for simplicity, we have a reference to Freeza to be able to call the transitionTo method in the different concrete states to transition between the states in which Freeza can be found. In this class, the abstract methods attack and defend are defined, which are the ones that will be implemented in each of the concrete states.

After defining the abstract class State we have to define each of the concrete states, which would be the five classes from Transformation1 to Transformation4 and the Golden Freeza transformation. Note that we have established the transition relationships between the different states, and it is very important to note that the states are known to each other, that is, the states that can be transitioned to are known from the origin state.

Lastly, we would have to look at the client class, which, although it is not part of the state pattern, we define it to know that this class will be the one that makes use of the State pattern, and specifically needs to know the Freeza and the initial state. Of course, if the initial state were not selected from the client, this class would only need to interact with the Freeza class without being aware of the states that the Freeza class may have.

Before leaving the UML class diagram, it is important to note that if we had a new Freeza transformation we would only have to implement the new state without having to modify the application. Therefore, we would be respecting the OCP since we can extend the software having it closed and protected as a base. In addition, the SRP is also respected because we have distributed the responsibility of each of the states to a specific class. Of course, our software right now is more cohesive.

And now, let’s move on to see our implemented.

import { State } from "./state";

export class Freeza {

private state: State;

constructor(state: State) {

this.transitionTo(state);

this.state.setFreeza(this);

}

isAlive(): boolean {

return this.state.getEnergy() > 0;

}

public transitionTo(state: State): void {

console.log('-----------------------------')

console.log(`Freeze: Transition to ${state.constructor.name}.`);

console.log('-----------------------------')

this.state = state;

this.state.setFreeza(this);

}

public attack(): void {

this.state.attack();

}

public defend(value: number): void {

this.state.defend(value);

}

}

Note that the Freeza class is now quite simple, there is the State attribute where responsibility has been delegated based on the state that Freeza is in. Note that the attack and defend methods only call the corresponding method of the abstract class, which will use one class or another depending on the state in which Freeza is. The transitionTo method assigns the state that Freeza is in.

Now we start to implement the Freeza states, first of all, the State abstract class is shown.

import { Freeza } from "./freeza";

export abstract class State {

abstract power: number;

abstract energy: number;

protected freeza: Freeza;

public setFreeza(freeza: Freeza) {

this.freeza = freeza;

}

public getEnergy() {

return this.energy;

}

public abstract attack(): void;

public abstract defend(value: number): void

}

In this class, we simply define the power and energy attributes as abstract and the attack and defend methods also as abstract since they will be the ones that are implemented in each concrete state. In addition, we have the reference to the Freeza object to be able to make the transition between states.

And now it would be necessary to see the implementation of the concrete states, we have defined five different states, which are the different transformations of Freeza, the logic is very simple and only for demonstration purposes. All of these states implement the attack and defend methods. In the attack methods, we calculate how Frieza will attack and how much energy would be restored, we are simply modifying these calculations.

On the other hand, the defend methods that are implemented, in our specific problem, apart from reducing the energy of Freeza, and transition between the different states. Of course, this part can be very different depending on our problem and our transition between different states.

Remember that design patterns are solutions that are repeated, and problems that appear in our software developments, but the intention of them must be understood and what problem it solves in order to later adapt them to our specific problems. So the difficulty is adapting the patterns to our specific problems, and you can’t take a solution with a design pattern and copy it directly because it probably doesn’t adapt well to our problem.

import { State } from "../state";

import { Transformation2 } from "./transformation2";

export class Transformation1 extends State {

power = 530000;

energy = 5;

public attack(): void {

const attackToEnemy = Math.round(this.power * (Math.random()/8));

const restoreEnergy = Math.round(Math.random());

this.energy = this.energy + restoreEnergy;

console.log('Freeza attack in the state form 1 -->', attackToEnemy);

console.log(`Freese restore energy ${restoreEnergy} and his energy is ${this.energy}\n`);

}

public defend(attack: number): void {

const attackFromEnemy = Math.round(attack * (Math.random()/7));

this.energy = this.energy - attackFromEnemy;

console.log('Freeza defend in form 1');

console.log(`Freeza received an attack of ${attackFromEnemy} and his energy is ${this.energy}\n`);

if(this.energy < 2){

this.freeza.transitionTo(new Transformation2());

}

}

}

import { State } from "../state";

import { Transformation1 } from "./transformation1";

import { Transformation3 } from "./transformation3";

export class Transformation2 extends State {

power = 106000;

energy = 10;

public attack(): void {

const attackToEnemy = Math.round(this.power * (Math.random()/7));

const restoreEnergy = Math.round(Math.random() * 2);

this.energy = this.energy + restoreEnergy;

console.log('Freeza attack in the state form 2 -->', attackToEnemy);

console.log(`Freese restore energy ${restoreEnergy} and his energy is ${this.energy}\n`);

}

public defend(attack: number) {

const attackFromEnemy = Math.round(attack * (Math.random()/6));

this.energy = this.energy - attackFromEnemy;

console.log('Freeza defend in form 2');

console.log(`Freeza received an attack of ${attackFromEnemy} and his energy is ${this.energy}\n`);

if(this.energy < 5){

this.freeza.transitionTo(new Transformation3());

}

if(this.energy > 20){

this.freeza.transitionTo(new Transformation1());

}

}

}

import { State } from "../state";

import { Transformation2 } from "./transformation2";

import { Transformation4 } from "./transformation4";

export class Transformation3 extends State {

power = 212000;

energy = 15;

public attack() {

const attackToEnemy = Math.round(this.power * (Math.random()/6));

const restoreEnergy = Math.round(Math.random() * 3);

this.energy = this.energy + restoreEnergy;

console.log('Freeza attack in the state form 3 -->', attackToEnemy);

console.log(`Freese restore energy ${restoreEnergy} and his energy is ${this.energy}\n`);

}

public defend(attack: number) {

const attackFromEnemy = Math.round(attack * (Math.random()/5));

this.energy = this.energy - attackFromEnemy;

console.log('Freeza defend in form 3');

console.log(`Freeza received an attack of ${attackFromEnemy} and his energy is ${this.energy}\n`);

if(this.energy < 5){

this.freeza.transitionTo(new Transformation4());

}

if(this.energy > 25){

this.freeza.transitionTo(new Transformation2());

}

}

}

import { GoldenFreeza } from "./golden-freeza";

import { State } from "../state";

import { Transformation3 } from "./transformation3";

export class Transformation4 extends State {

power = 406000;

energy = 20;

public attack() {

const attackToEnemy = Math.round(this.power * (Math.random()/5));

const restoreEnergy = Math.round(Math.random() * 4);

this.energy = this.energy + restoreEnergy;

console.log('Freeza attack in the state form 4 -->', attackToEnemy);

console.log(`Freese restore energy ${restoreEnergy} and his energy is ${this.energy}\n`);

}

public defend(attack: number) {

const attackFromEnemy = Math.round(attack * (Math.random()/6));

this.energy = this.energy - attackFromEnemy;

console.log('Freeza defend in form 4');

console.log(`Freeza received an attack of ${attackFromEnemy} and his energy is ${this.energy}\n`);

if(this.energy < 5){

this.freeza.transitionTo(new GoldenFreeza());

}

if(this.energy > 25){

this.freeza.transitionTo(new Transformation3());

}

}

}

import { State } from "../state";

import { Transformation4 } from "./transformation4";

export class GoldenFreeza extends State {

power = 812000;

energy = 30;

public attack() {

const powerAttack = Math.round(this.power * (Math.random()/4));

const restoreEnergy = Math.round(Math.random() * 5);

this.energy = this.energy + restoreEnergy;

console.log('Freeza attack in the state Golden Freeza -->', powerAttack);

console.log(`Freese restore energy ${restoreEnergy} and his energy is ${this.energy}\n`);

}

public defend(attack: number) {

const attackFromEnemy = Math.round(attack * (Math.random()/5));

this.energy = this.energy - attackFromEnemy;

console.log('Freeza defend in Golden Freeza');

console.log(`Freeza received an attack of ${attackFromEnemy} and his energy is ${this.energy}\n`);

if(this.energy > 50){

this.freeza.transitionTo(new Transformation4());

}

}

}

The last step would be to see the class that makes use of our Freeza object. This class is often called the client, and in our case it hasn’t changed at all between the version without and with the application of the design pattern.

import { Freeza } from "./freeza";

import { Transformation1 } from "./states/transformation1";

const sleep = (ms: number) => new Promise((r) => setTimeout(r, ms));

const freeza = new Freeza(new Transformation1()); // Initial State

(async () => {

while(freeza.isAlive()){

freeza.attack();

await sleep(1000);

freeza.defend(10);

await sleep(1000);

}

})();

Finally, I’ve created several npm scripts through which the code presented in this article can be executed:

npm run example1-problem

npm run example1-state-solution-1

npm run example2-problem

npm run example2-state-solution-1

See this GitHub repo for the full code.

Conclusion

State is a design pattern that allows you to respect the Open-Closed Principle since a new State can be created without breaking the existing code. In addition, this allows you to comply with the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) since each State only has a single responsibility to resolve. Another very interesting point of this pattern is that the states can interact with each other, transitioning between the different states.

The most important thing about this pattern is not the concrete implementation of it but the ability to recognize the problem that this pattern can solve and when it can be applied. The specific implementation isn’t as important since that will vary depending on the programming language used.